A review of the partnership literature reveals that there are considerable variations amongst the many definitions of what constitutes a PPP. The widespread use of the term public-private-partnership hides important differences between the different forms of public private collaboration (Schaeffer & Loveridge, 2002). While a unifying theme of these definitions is that all arrangements involve at least one public partner and one private partner; oftentimes, that is where the similarities end. In support of this perception, the following definitions of PPP will suffice:

- Van Ham and Koppenjan (2001) identify PPP as ‘cooperation of some sort of durability between public and private actors in which they jointly develop products and services, and share risks, costs, and resources which are connected with the desired products.

- According to McMillan (2003), PPP is an agreement between government and the private sector regarding the provision of public services or infrastructure.

- The government of India in ADB workshop report (2006) sees Public Private Partnership (PPP) project as one based on a contract or concessional agreement between a Government or statutory entity on the one side, and a private sector company on the other side, for delivering an infrastructure and services on payment of user charges.

- In Wikipedia (2017), it was stated that PPP is a contract between a public sector authority and a private party, in which the private party provides a public service or paper and assumes substantial financial, technical and operational risk in the paper.

What can be deduced from these definitions is that PPP concerns a partnership between the public sector and the private sector entity, whereby, risks and responsibilities are shared for mutual benefits; a collaborative arrangement between government and one or more private parties; or a co-operative ventures between a public entity and a private party, aiming to realize common purpose in which they share risks, costs, and profits. Thus, it is a means of bringing together social priorities with the managerial skills of the private sector, thus relieving government of the burden of large capital expenditure, and transferring the risk of cost overruns to the private sector. In this kind of partnership, rather than completely transferring public assets to the private sector, as with privatization, government and businessmen work together to provide services to the public. The system has been criticized for blurring the lines between public and private provision, leading to a lack of accountability with regard to funding, risk exposure, and the performance of such projects.

The next part of this paper will explore how the concepts of PPPs are viewed in each of these approaches (Teisman & Klijin, 2002).

a) Public Private Partnership (PPP) – A Tool of Governance or Management: A popular way of defining PPP is as a tool of governance or management. The dominant theme is that PPP provides a novel approach to delivering goods and services to citizens, and the novelty being the mode of managing and governing (Hodge & Greve, 2005). The authors who utilise this approach to PPP tend to focus on the organisational aspects of the relationship. Most definitions that focus on governance and management tools emphasise that PPPs are either inter-organisational or financial arrangement between the public and private actors.

There are some common agreements in most PPP literature which focus on inter-organisational arrangements. First, PPP is cooperation between organisations. The second aspect is sharing risks. Risk sharing is viewed as an important incentive for both the public and private sectors, since it is assumed that risk sharing could benefit both actors. The third prospect is that these types of cooperation can result in some new and better products or services that no single organisation either the public or the private could produce better alone. Finally, it has been noted that in a PPP a partnership involves a longer-term commitment which can continue for a number of years, say, for 10 to 30 years.

Finally, the Dutch Public Management Scholars, Van Ham and Koppenjan (2001) definition of PPP emphasised organisational relationships. They identify PPP as ‘cooperation of some sort of durability between public and private actors in which they jointly develop products and services, and share risks, costs, and resources, which are connected with these products’. This definition has several features. First, it underlines cooperation of some durability, where collaboration cannot only take place in short-term contracts. Second, it emphasizes risk-sharing as a vital component. Both parties are in a partnership together had to bear parts of the risks involved. Third, they jointly produce something (a product or a service) and, perhaps implicitly, both stand to gain from mutual effort. Similar features are evident in the definitions of PPPs that are provided by Klijn and Teisman (2002), where PPPs are described as ‘sustainable cooperation between public and private actors in which joints and/or services are developed and in which risks, costs and profits are shared and as ‘a risk-sharing relationship between the public private – including voluntary sector to bring about a desired public policy outcome.

b) Public Private Partnership (PPP) – Tool of Financial Arrangements: Some definitions of PPP stress the financial relationships. There are promises that PPP reduces pressure on government budgets because of using private finance for infrastructures and they also provide better value for money in the provision of public infrastructure. These usages of PPPs are prominent in the literatures on infrastructure building. These mostly include BOT (Build-Operate-Transfer), BOOT (Build-Own-Operate-Transfer) and BOO (Build-Own-Operate). The most common of these arrangements is BOT. Campbell (2001) suggests a definition of PPP focusing on financial arrangements; that is, ‘a PPP project generally involves the design, construction, financing and maintenance and in some cases operation of public infrastructure or a public facility by the private sector under a long term contract’. There are other modes of financial arrangements in PPPs, in which both public and private actors are involved in financing.

Collin (1998) defined Public-Private Partnership as an arrangement between a municipality and one or more private firms where all parties were involved in sharing risks, profit, utilities and investments through joint ownership. There are several aspects to this definition. First: it is emphasizing on sharing, such as risk sharing, profit sharing, and sharing of utilities. Second, it underlines the joint ownership of organisations in a PPP project. Finally, the most important aspect is the financial investment of all organisations.

c) Public Private Partnership (PPP) – A Tool of Development Process: Public Private Partnership (PPP) is emerging as a new development arrangement. The prominent arguments are PPPs maximise benefits for development through collaboration and enhanced efficiency. Thus PPP is seen as a significant method of promoting development and a tool for development (Paoletto 2000). ADBI studied several public private partnerships programmes in Asia and the Pacific and defines PPP as: ‘collaborative activities among interested groups and actors, based on a mutual recognition of respective strengths and weaknesses, working towards common agreed objectives developed through effective and timely communication. There are several features in this definition.

- First, common objectives – partnerships are undertaken for the purposes of implementing objectives that have been agreed to by the groups involved. The objectives are ideally developed through a process of communication and negotiation that is acceptable to all actors involved.

- Second, agreement to undertake activities means that there will be specific commitment to undertake activities and these activities will be built on each partner’s strengths.

- Third, actions of these PPP will be to overcome weaknesses of each partner – overcoming apparent weaknesses may involve a sharing of expertise, knowledge or experiences by one or more groups amongst the other groups. It also means first recognising the weaknesses.

- Fourth, actors in this process of partnership may include different community groups such as NGOs, local governments, research and developments institutes, and national governments. The World Bank’s definition of PPP is closely aligned to that of the ADBI.

The World Bank (1999) defines PPP as joint initiatives of the public sector in conjunction with the private, for profit and not-for-profit sectors, also referred to as the government, business and civic organisations. In these partnerships, each of the actors contributes resources (finance, human, technical and intangibles, such as information or political support) and participates in the decision making process.

d) Public Private Partnership (PPP) – a Language Game: Another alternative view of PPP is as a language game. The language of PPP is a game designed to ‘cloud’ other strategies and purposes. One such purpose is privatisation and the encouragement of private providers to supply public services at the expense of public organisations. Privatisations are terms that generate opposition quickly and that expression such as ‘alternative delivery system’ or PPPs are more acceptable. Savas (2000) considers that now PPPs enable private organisations to get a market share of public service provision; however, he states that ‘PPPs invite more people and organisations to join the debate’. Thus, Teisman and Klijn (2002) and Savas (2000) writing from different perspectives, all agree that the use of the term ‘public–private partnership’ (PPP) can be seen as a pejorative term like ‘contracting out’ and ‘privatization’.

Types of Public-Private Partnerships

PPPs may be employed for the delivery of social services or the construction, operation and/or maintenance of public infrastructure (such as transportation, power, water/wastewater or public buildings). In some cases, both infrastructure and service requirements can be combined into a single partnership. There are various types of public private partnership which have been described by various authors but in this study, public private partnership types are seen in the view of United States General Accounting Office Glossary (1999) to include:

- Build-own-operate (BOO): Under a BOO arrangement, the contractor constructs and operates a facility without transferring ownership to the public sector. Legal title to the facility remains in the private sector, and there is no obligation for the public sector to purchase the facility or take title. A BOO transaction may qualify for tax-exempt status as a service contract if all Internal Revenue Code requirements are satisfied.

- Build Own Operate Transfer: Projects of the Build-Own-Operate–Transfer (BOOT): This type involves a private developer financing, building, owning and operating a facility for a specified period. At the expiration of the specified period, the facility is returned to the Government.

- Build/operate/transfer (BOT) or Build/transfer/ operate (BTO): Under the BOT option, the private partner builds a facility to the specifications agreed to by the public agency, operates the facility for a specified time period under a contract or franchise agreement with the agency, and then transfers the facility to the agency at the end of the specified period of time. In most cases, the private partner will also provide some, or all, of the financing for the facility, so the length of the contract or franchise must be sufficient to enable the private partner to realize a reasonable return on its investment through user charges. At the end of the franchise period, the public partner can assume operating responsibility for the facility, contract the operations to the original franchise holder, or award a new contract or franchise to a new private partner. The BTO model is similar to the BOT model except that the transfer to the public owner takes place at the time that construction is completed, rather than at the end of the franchise period.

- Design, build, finance and operate (DBFO): A contract let under the principles of the private finance initiative whereby the same supplier undertakes the design and construction of an asset and thereafter maintains it for an extended period, often 25 or 30 years.

- Build operate (BO): A BO transaction is a form of asset sale that includes a buy rehabilitation or expansion of an existing facility. The government sells the asset to the private sector entity, which then makes the improvements necessary to operate the facility in a profitable manner.

- Contract services operations and maintenance: A public partner (federal, state, or local government agency or authority) contracts with a private partner to provide and/or maintain a specific service. Under the private operation and maintenance option, the public partner retains ownership and overall management of the public facility or system, but the private party may invest its own capital in the facility or system. Any private investment is carefully calculated in relation to its contributions to operational efficiencies and savings over the term of the contract. Generally, the longer the contract term, the greater the opportunity for increased private investment because there is more time available in which to recoup any investment and earn a reasonable return. Many local governments use this contractual partnership to provide wastewater treatment services.

- Design-build-operate (DBO): In a DBO project, a single contract is awarded for the design, construction, and operation of a capital improvement. Title to the facility remains with the public sector unless the project is a design/build/operate/transfer or design/build/own/operate project. The DBO method of contracting is contrary to the separated and sequential approach ordinarily used in the United States by both the public and private sectors. This method involves one contract for design with an architect or engineer, followed by a different contract with a builder for project construction, followed by the owner’s taking over the project and operating it.

A simple design-build approach creates a single point of responsibility for design and construction and can speed project completion by facilitating the overlap of the design and construction phases of the project. On a public project, the operations phase is normally handled by the public sector or awarded to the private sector under a separate operations and maintenance agreement. Combining all three phases into a DBO approach maintains the continuity of private sector involvement and can facilitate private-sector financing of public projects supported by user fees generated during the operations phase.

- Developer financing: Under developer financing, the private party (usually a real estate developer) finances the construction or expansion of a public facility in exchange for the right to build residential housing, commercial stores, and/or industrial facilities at the site. The private developer contributes capital and may operate the facility under the oversight of the government. The developer gains the right to use the facility and may receive future income from user fees. While developers may in rare cases build a facility, more typically they are charged a fee or required to purchase capacity in an existing facility. This payment is used to expand or upgrade the facility. Developer financing arrangements are often called capacity credits, impact fees, or exactions. Developer financing may be voluntary or involuntary depending on the specific local circumstances.

- Enhanced use leasing (EUL): A EUL is an asset management program in the Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA) that can include a variety of different leasing arrangements (e.g., lease/develop/operate, build/develop/operate). EULs enable the DVA to long-term lease DVA-controlled property to the private sector or other public entities for non-DVA uses in return for receiving fair consideration (monetary or in-kind) that enhances DVA’s mission or programs.

- Lease/develop/operate (LDO) or Build/develop/operate (BDO): Under these partnership arrangements, the private party leases or buys an existing facility from a public agency; invests its own capital to renovate, modernize, and/or expand the facility; and then operates it under a contract with the public agency. A number of different types of municipal transit facilities have been leased and developed under LDO and BDO arrangements.

- Lease/purchase: A lease/purchase is an instalment-purchase contract. Under this model, the private sector finances and builds a new facility, which it then leases to a public agency. The public agency makes scheduled lease payments to the private party. The public agency accrues equity in the facility with each payment. At the end of the lease term, the public agency owns the facility or purchases it at the cost of any remaining unpaid balance in the lease. Under this arrangement, the facility may be operated by either the public agency or the private developer during the term of the lease. Lease/purchase arrangements have been used by the General Services Administration for building federal office buildings and by a number of states to build prisons and other correctional facilities in the USA.

- Sale/leaseback: A sale/leaseback is a financial arrangement in which the owner of a facility sells it to another entity, and subsequently leases it back from the new owner. Both public and private entities may enter into sale/leaseback arrangements for a variety of reasons. An innovative application of the sale/leaseback technique is the sale of a public facility to a public or private holding company for the purposes of limiting governmental liability under certain statutes. Under this arrangement, the government that sold the facility leases it back and continues to operate it.

- Tax-exempt lease: Under a tax-exempt lease arrangement, a public partner finances capital assets or facilities by borrowing funds from a private investor or financial institution. The private partner generally acquires title to the asset, but then transfers it to the public partner either at the beginning or end of the lease term. The portion of the lease payment used to pay interest on the capital investment is tax exempt under state and federal laws. In the USA, tax-exempt leases have been used to finance a wide variety of capital assets, ranging from computers to telecommunication systems and municipal vehicle fleets.

- Turnkey: Under a turnkey arrangement, a public agency contracts with a private investor/vendor to design and build a complete facility in accordance with specified performance standards and criteria agreed. The private developer commits to build the facility for a fixed price and absorbs the construction risk of meeting that price commitment. Generally, in a turnkey transaction, the private partners use fast-track construction techniques (such as design-build) and are not bound by traditional public sector procurement regulations. This combination often enables the private partner to complete the facility in significantly less time and for less cost than could be accomplished under traditional construction techniques. In a turnkey transaction, financing and ownership of the facility can rest with either the public or private partner. For example, the public agency might provide the financing, with the attendant costs and risks. Alternatively, the private party might provide the financing capital, generally in exchange for a long-term contract to operate the facility.

Forms of Public Private Partnerships

According to the NASCIO issue brief (2006), public-private-partnerships can take various forms. This include both collaborative (non-legal binding) or contractual (legally binding) agreements.

a) Contractual partnerships: the traditional view: Depending on the type of contract, the following levels of contractual partnerships exist:

- Time and materials (T&M): Under this type of contractual partnership, the public sector customer has the most control during the term of the relationship. There are no performance-based measured outcomes; thus, performance thresholds have not been identified, and there are no reporting mechanisms for performance.

- Firm fixed price (FFP): Under this type of contractual partnership, the public sector customer has less control and must define the deliverable for the contractor. Outcomes are identified as “deliverables”, and typically not in the form of metrics nor are they measured during the course of the contract. There is a desired “to-be” state in mind, but uncertainty regarding “how” to reach those outcomes is assumed by the private sector supplier.

- Performance based: This type of contractual partnership is actually a marriage of T & M and FFP with joint solution design meetings and mutually agreed upon Service Level Agreements (SLAs). Performance thresholds and reporting mechanisms are jointly established between public sector customer and private sector supplier, there are stated objectives and outcomes by the public sector, and performance is measured on a predetermined and consistent basis.

- Shared-in-services savings: Under this type of contractual partnership, the public sector customer has relinquished control to the private sector supplier and the private sector supplier assumes most or all of the risk in this contractual scenario. This arrangement is usually referred to as an A-76 in the federal government – a total outsourcing arrangement. The private sector supplier has the most control and the public sector customer should justify this arrangement by knowing their total cost of ownership of doing this business before outsourcing.

b) Collaborative partnerships: Collaborative partnerships are non-legal working relationships that often occur between the public and private sectors to meet a common objective or goal. Primarily goodwill gestures, collaborative partnerships are often used to provide knowledge exchange or collective leverage resources for a specified goal. It is not uncommon for technology firms and state IT organisations to collaborate to explore new technology that mutually benefits both parties. For example, organisations often establish an advisory board, stakeholder group or governance body which includes private sector representatives. These groups may be formed to assist with strategic planning, to provide on-going expertise and guidance, or to target specific issues or projects. These bodies may be standing committees or they may be task forces, convened for short term, tactical purposes.

No matter what the title or structure of these entities, they create an environment to foster collaboration and partnerships. These collaborative efforts provide an open forum for both public and private entities to exchange ideas and promote the interest of the technology community and government to provide better services and meet new citizen demands.

According to NCPPP (2002), there are six critical components of any successful Public-Private Partnership (PPP). While there is not a set formula or an absolute foolproof technique in crafting successful PPPs, each of these keys is involved in varying degrees.

- Statutory and political environment: A successful partnership can result only if there is commitment from the “top”. The most senior public officials must be willing to be actively involved in supporting the concept of PPPs and taking a leadership role in the development of each given partnership.

- Public sectors organised structure: Once a partnership has been established, the public-sector must remain actively involved in the project or program. On-going monitoring of the performance of the partnership is important in assuring its success. The monitoring frequency (daily, weekly, monthly or quarterly basis) is often defined in the business plan and/or contract.

- Detailed business plan (contract): A carefully developed plan (often done with the assistance of outside experts in this field) will substantially increase the probability of success of the partnership. The plan most often will take the form of an extensive, detailed contract; clearly describing the responsibilities of both the public and private partners. In addition to attempting to foresee areas of respective responsibilities, a good plan or contract will include clearly defined method of dispute resolution (because not all contingencies can be foreseen)

- Guaranteed revenue stream: While the private partner may provide the initial funding for capital improvements, there must be a means of repayment of this investment over the long term of the partnership. The income stream can be generated by a variety and combination of sources (fees, tolls, tax, increment financing, or a wide range of additional options) but must be assured for the length of the partnership.

- Stakeholder support: More people will be affected by a partnership than just the public officials and the private-sector partner. Affected employee, members of the public receiving the services, the press, appropriate labour unions and relevant interest groups will have opinions and frequently significant misconceptions about a partnership and its value to all the public. It is important to communicate openly and candidly with these stakeholders to minimize potential resistance to establishing a partnership.

- Careful selection of partner: The decision process in selecting a private sector partner should be open and transparent, aiding in building the credibility of the project and partners with the full range of stakeholders. The “lowest bid” is not always the best choice for selecting a partner. The “best value” in partner is critical in a long-term relationship that is central to a successful partnership. A candidate’s experience in the specific area of partnerships being considered is an important factor in identifying the right partner (NCPP 2002

Benefit and risks associated with PPP Projects

The decision to enter into a PPP arrangement according to The Guardian (2011) is driven by two major criteria:

- Will the quality of service provided by the private sector continue to meet/exceed government and he general public’s expectations?

- Will the service provision provide value for money or both the government and general public?

For the government, value for money will be achieved if the provision of services under private sector management results in cost savings and improves service quality to the general public.

Benefits associated with PPP to the public sector

- Transfer of financial and non-financial risks: A core principle of any PPP arrangement is the allocation of risk to the party best able to manage it, at the least cost Under PPP, the government is able to outsource the construction and management risks to the private sector, but can withhold service payments and apply financial penalties (liquidation damages) if the private sector fails to meet agreed service quality levels. Initial PPP projects in UK; and Australia saw governments attempt to transfer an excessive proportion of risk to the private sector, which unreasonably threatened the financial viability of the projects. More recent deals seek an optimal, rather than excessive risk transfer arrangement.

- Cost Savings: Governments (globally) are traditionally poor at procuring infrastructure services and a result cost blowouts are common with public or assets. The private sector is much more expensed in managing costs.

- Enhanced asset quality and service levels provided to the public: The private sector remains responsible for ensuring that the public asset and services livered meet certain quality benchmarks throughout the life of the PPP agreement, Therefore, it is in their interest to ensure that the assets are constructed to a high quality standard, utilizing the best technology so as to minimise the re maintenance costs. PPP contracts also typically include conditions requiring the private operator to upgrade the facilities throughout. Unless specifically dealt with in the contract, upgrading to satisfy these benchmarks is typically funded by the private sector.

- Government expenditure: PPP frees up fiscal funds for other areas of public expenditure and proves cash flow management as the periodic vice payments over the life of the agreement lace the significant up-front capital expenditure as well as recurring expenditure for maintenance. This also has obvious accounting Benefits; the asset is off balance sheet.

Risks Associated with PPP to the public sector

- Risk of private sector failure: In this instance, the PPP contract with the private operator is either terminated or suspended, resulting in the government being forced to step in and recommence providing the services to the public. This normally results in public criticism and further financial loss. It is therefore imperative that the government is knowledgeable and confident that all parties involved in the private sector consortium are sufficiently competent and financially capable of delivering services to the predetermined specifications.

- Risk of service quality standards falling: In general, government largely overcomes this by retaining the right to withhold service payments if service quality levels are not met over the whole life of the contract. In most PPP contracts, the payment mechanism will include a series of deductions that can be made by the government depending on the severity of the service quality breach. For assets where private sector revenue is levied directly on the general public users, falling service quality standards remain a risk Political Public sector employees who are either forced to move into the private sector or become unemployed (supported by their representative trade unions) may present a significant obstacle to PPP projects.

- Private sector monopolies forming: Where certain companies secure a series of major PPP contracts in any given sector, there is a risk that monopolies may form, resulting in potential price manipulation and lower standards of service quality to the general public users.

Benefits Associated with PPP to the Private Sector

PPP provides the private sector with access to large scale public construction projects that, if priced accurately and costs managed effectively can deliver reasonable, long term revenue and profit. In addition, most PPP arrangements allow for incentive payments based on a range of pre-agreed criteria. To ensure the financial stability of private sector participants in PPP projects, it is critical that the government considers the profitability requirements of the companies involved in the private consortium.

Risks associated with PPP to the private sector

- Revenue risks: For projects where the key source of revenue to the private operator is generated from tariffs {tolls and charges} levied on asset or service usage (e.g. roads, rail, water, energy), historical and future usage patterns and permitted tariff charges will be the factors in determining overall project profitability. There are often practical difficulties in forecasting usage (e.g. when new competing infrastructure is built) and political difficulties in rising tariffs. In the event that services provided fail to meet quality standards, the government may withhold payment and/or impose liquidated damages.

- Financing risks: Construction or acquisition public sector assets normally requires high levels of debt Under PIT, this can be a mix of public and private debt but in all cases the private debt funding component must and will be higher than the public component. Interest rates for private sector funding are normally higher than public sector borrowing rates. Loan term facilities are commonly extended for 25-30 years. However, refinancing may expose the private sector consortium to certain interest rate risks. In the event of a major problem on the project, financiers may call for partial or full repayment of debt and therefore challenge the going concern status of the project.

- Delayed cash inflow: The SPV will not usually begin to receive payments or tariff revenue until the asset is completed and service is provided at a level of quality that meets government expectations. Therefore the construction must be completed as quickly as possible, but also at a high quality standard so that future maintenance costs are minimized.

- Dispute resolution: Generally, most PPP contracts enable governments to step-in and assume direct responsibility for service delivery in the event that the private sector fails to meet agreed service levels. However, experience has shown that governments have often been less successful than the private sector in resolving the crises and in some cases have contributed to deterioration in operating and financial performance. The allocation of financial liability becomes difficult and the private sector may be held liable for further losses generated under the government’s management. The private sector will often seek to mitigate their exposure by imposing cure rights in the concession agreement, such that governments agree to reduce the liability of the operator to the extent that they are directly responsible for the loss or damage following a step-in scenario.

- Other unforeseen risks: Prior to entering into any long term PPP contract, the private sector participants, must ensure that they understand all the risk that are faced and have priced them accord. They must try to avoid accepting response risks that are not within their control that the service payment price or tariff revenue is adequate to cover all unforeseen additional future costs. The definition and recourse for regulatory changes (e.g. environmental) and other force majeure events must be clearly addressed in the legal agreements.

References

ADB Workshop Report (2006). Facilitating public private partnership for accelerated infrastructure development in India, Regional Workshops of Chief Secretaries on Public Private Partnership.

Asika, N. (1991). Research methodology in behavioural science. Lagos: Longman Publishing Limited.

Campbell, G. (2001). Public private partnership – A developing market? Melbourne, Unpublished Paper.

Carr, G. (1998). Public private partnership: The Canadian experience. Presentation to the Oxford School of Project Finance Oxford.

Collin, S. E. (1998). In the twilight zone: A survey of public private partnership in Sweden. Public Productivity and Management Review. Vol. 21.

Hall, D., de la Motte, R. & Davies, S. (2003). Terminology of public-private partnerships (PPPs). Public Services International Research Unit (PSIRU), School of Computing and Mathematical Sciences, University of Greenwich, Park Row, London SE10 9LS U.K. www.psiru.org

Hawkins, J. (1995). Oxford mini-reference dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hodge, G. A. & Greve, C. (2007). Public private partnership: An international performance review. Public Administration Review.

Ipaye, O. (2008). The relevance of research in real estate practice. Being a National Diploma Dissertation submitted to the Department of Estate Management, Yaba College of Technology, Yaba – Lagos.

Khanom, N. A. (2010). Conceptual issues defining public private partnership. International Review of Business Research Papers, Volume 6. Number 2.

McMillan, A. in Oxford Dictionary of Politics Via Google.Com, Retrieved on 10th July, 2011.

NASCIO Issue Brief (2006). Keys to collaboration: Building effective public private partnerships.

Ncfnigeria.com (n.d.). Lekki conservation centre, Lagos. Retrieved on the 15th of November, 2011 from www.ncfnigeria.com via google.com

Olusegun, K. (2011). Estate office practice. Lagos: Adro Dadar Heritage Company Limited.

Paoletto, G. (2000). Public private partnerships: An overview of cause and effect in Wang, Indian Odi, Public Private Partnerships in Social Sector.

Phillips Neal, E.M. (2010). Playtime preservation: Public private partnership in public land management. Being a PhD dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy to Northeastern University, Boston, Massachusetts.

Savas, A. (2000). Privatization and public private partnership: New York: Chatham House Publishers.

Shaeffer, P. V. & Loveridge, S. (2002). Towards understanding of types of public private cooperation. Partnership performance and Management System. Vol. 26 No. 2.

Teiseman, G. and Klyn, E.H (2002). Partnership agreements: Governmental rhetoric or governance scheme? Public Administration Review, Vol. 62, No. 2.

The Guardian Newspaper (January 29, 2011). Article on public private partnership on the 29th of January 2011. Pp. 29-30.

Thorncroft M. (1965). Principles of estate management. London: Estate Gazette Limited.

Tripadvisor.com (n.d.). The Lekki Conservation centre. Retrieved on the 15th of November, 2011 from www.tripadvisor.com via google.com.

Van Dijk M.P. (2010). Public private partnership in basic service delivery: impact on the poor, Examples from Water Sector in India. Retrieved from danapraire.com.

Wikipedia.org (2015). The Free Encyclopedic: Natural Endowment. Retrieved on the 23rd of March, 2015.

Wikipedia.org: The Free Encyclopaedia: The concept of public private partnership. Retrieved on the 14th of July, 2011 from www.wikipedia.org

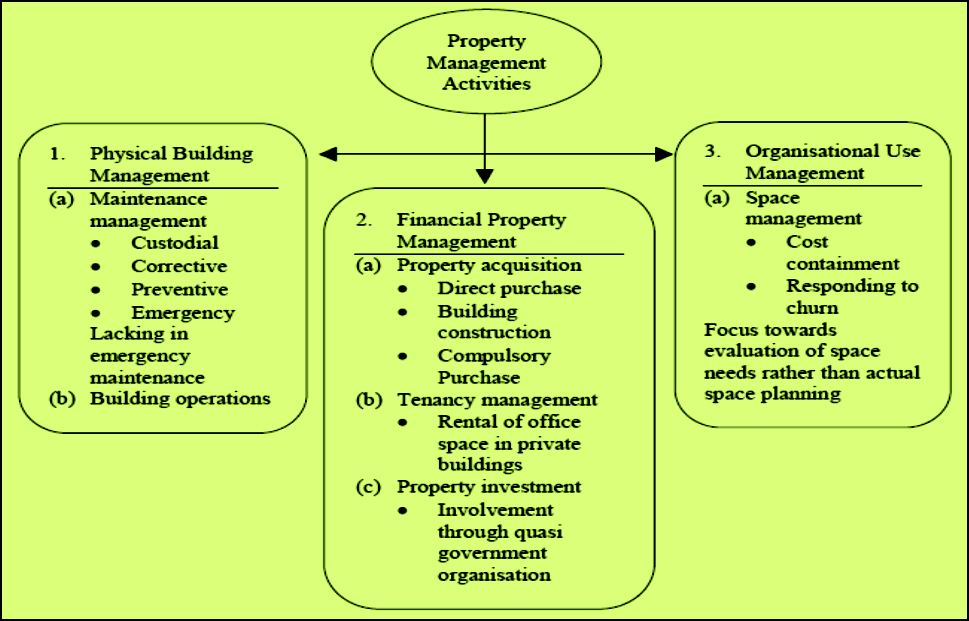

PM Activities (Isa, no date, in Olusegun, 2015)

Property management may involve seeking out tenants to occupy the space, collecting monthly rental payment, maintaining the property, and upkeep of the grounds. Thus, property management is the administration of residential, commercial and industrial real estate including apartments, detached houses, condominium units and shopping centers. Furthermore, property management entails the management of personal property, equipment, tooling and physical capital assets that are acquired and used to build, repair and maintain end item deliverables. Property management involves the processes, systems and manpower required to manage the life cycle of all acquired property as defined above including acquisition, control, accountability, responsibility, maintenance, utilisation and disposition.

Principles of ‘Management’ for Property Management Companies

Most of the property management companies often follow specific property management principles to enable them deliver their management services for those properties that need them within the market. Outlined below are some of the principles that are usually employed by property management companies: · Principle of division of work: Most of these companies have divided the operations into departments to enable them work more efficiently. Through the departments, they have delegated work to ensure that all employees contribute positively to the operations within the company thus enhancing their job their performance. · Principle of authority and responsibility: Most of these companies often understand the importance of principle of authority and responsibility when managing their operations in the real estate market. · Discipline in their management roles: The principle of discipline often plays an important role in the success of every company whenever they operating in the real estate industry. Discipline the mission and vision of the company always plays an important role whenever they are operating within the market. Most of these companies have always ensured that they achieve their set goals. · The degree of centralisation: The amount of company power that is wielded with central management often depends on the size of the company. Centralisation often implies concentration of authority of decision making at the top the company’s management. Sharing of the authority with the lower levels is known as decentralisation of real estate companies. The companies often work hard to achieve that proper balance. · Subordination of the individual interest: The management of these companies must always put aside their personal considerations by putting the company objectives first. Hence, the interests of goals of company must always prevail over the individuals interests when operating to allow the company to grow in the real estate industry. |

There are two major branches of property management – logistical and physical.

- Logistics of property management: A key factor in the logistics of property management is financial reporting. Financial reporting must be timely and accurate to be effective. Regular and comprehensive reporting establishes continuity and reduces the number of lines of communication, thus maximising time and minimising confusion. Such reports should always adhere to GAAP (General Accepted Accounting Principles), though employing a higher set of standards for quality assurance is also ideal. Specific reports, such as cash to budget variances, cash flow and income statements, balance sheets, and complete transactional accounting registers, are fundamental and essential to the property management process. In addition to financial reporting, up-to-date property management software is an important part of logistics. It enables customized reporting for each type of property managed. Investing in infrastructure is critical to managing a diverse portfolio. The more quickly a property management system can identify problems and produce solutions, the more successful a project can be. Further logistical involvement is necessary in developing bid specifications, securing competitive bids, and coordinating with contractors, vendors and suppliers.

- Physical aspect of property management: Beyond the logistical or back-end component of successful property management is the physical component. Preserving, maintaining, protecting and enhancing the physical and financial aspects of real estate holdings is of paramount importance. Without corresponding efforts in logistical and physical property management, neither can achieve complete success. This includes emergency management as well as regular visitations and inspections of the property. Comprehensive inspections deliver far-reaching results, and should include lobbies, stairwells, landscaping, recreation facilities, walks and driveways, parking lots, and other physical aspects of the real estate.

The object of property management

Property management has to do with maintaining both the physical and economic life of the property, so that it will be put to a reasonable level of good use and optimum, envisaged return. In the management of real estate assets, there are a lot of derivable outcomes, which could be the collection of periodic rental income at a minimal expense, to maintain the valve of the property by spending wisely on maintenance, to secure the co-operation of tenants and/or occupiers in order to avoid neglect and voluntary wastes, etc.

Excellent property management would entail:

- Putting the property in sound physical footing through proper orchestrated maintenance and upkeep of the physical property.

- Putting the property in sound economic footing through ensuring optimum returns from the property investment.

- Taking away, as much as possible, inherent management problems from the property owner who may have other life endeavours, which may be engaging his/her attention; or who may not be very knowledgeable in the different facets of property management activities.

- Maintaining good tenant and public relationship.

Some of the basic principles that underlie all good property management solutions:

- Effective, responsive and customised service.

- Strength, generated from team effort and training.

- Creativity and understanding of management principles.

- Goals to enhance the value and aesthetics of a property.

- Constant re-evaluation of procedures to ensure superior levels of quality.

Property Management activities

As stated in the Business Dictionary (2000), PM is the operation of property as a business, which necessitates the performance of the following two main tasks; namely: accounting and reporting, leasing, maintenance and repairs, paying taxes, provision of utilities and insurance, remodelling, rent setting and collection; and Property portfolio management tasks including acquisition and disposition, development and rehabilitation feasibility, financing and income tax accounting. PM focuses on the physical building management, financial property management and organisational use management.

The function of property management as performed by professional Property Managers on behalf of building owners include:

- Collection of rents for property owners: This is an important assignment (not necessarily the only function), for without rent to meet mortgage interest, repairs and maintenance; there is no point wasting one’s time as Property Manager.

- Tenant’s selection: There should be an adequate and careful tenant selection programme to avoid the problem of default in the periodic rent payment.

- Control and supervision of building repairs and maintenance including ordering, measuring of works through proper and effective maintenance system. In the context of building maintenance, the function of Property Manager is to maintain the building to an appropriate and acceptable standard at reasonable cost and with the minimum of inconvenience to the occupiers.

- Keeping and rendering of proper records such as service charge accounts, rent accounts, work order forms, etc.

- Budgeting records: the Property Manager prepares the budget, cash flow and cost control to deal effectively with income and expenditure issues.

- Appointment of bills: The appointment of electricity bill, water bill, tenement rate to the building occupiers based on their respective consuming proportions and to ensure prompt payment of rates and other taxes by such occupiers.

Other property management functions are:

- Periodic rent reviews in tandem with economic realities, and in line with lease terms.

- Arbitration services

- Attending to matters requiring consent of the property owner

- Negotiation of leases of vacant accommodation

- Liaising with other adjoining property owners on issues of mutual interest to the adjoining owner and his client.

- Routine inspection.

- Fixing of service charge and management of service charge account.

- Planning, development or redevelopment, as the situation may demand.

- Security of premises

- Documentation of all transaction carried out on a property.

- Ensuring that tenants pay their rates and taxes regularly.

- Preparation of schedule of dilapidation as at when necessary and adequately advise his client on same.

- Control and supervision of maintenance works.

- Giving of advice to client(s) or tenants on ensuring peaceable occupation etc.

- Ensuring that the surroundings of the property is regularly cleared of weeds, refuse and that the common areas are routinely swept and dusted.

In conclusion, the property manager’s function can be summed up as that of trying to consciously increase returns (through effective property management portfolio in the areas of, property expansion or outright redevelopment, etc.), and trying to be economically prudent, and maintaining high returns through ‘highest and best use’ of the property being maintained.

Reasons for Hiring a Property Manager

Managing a property often involves a variety of administrative tasks, including handling property maintenance, supervising building repairs and ensuring outgoing expenses are paid. Owners who desire to rent their properties to tenants may use the services of a property management company. These types of companies can provide services such as:

- Rent collection: A professional property management company have systems and strategies to improve rent collection and on-time rent payments. This ensures consistent rent collection. Quick and consistent rent collection is absolutely critical in this real estate market where good cash flow can mean the difference between success and failure as a real estate investor.

- Local knowledge of rental rates: Property Management Company have extensive local knowledge of rents and the ability to determine the highest rental rate possible for your property. With the internet and the ability to do large scale searches for rental properties, potential tenants know if your property is overpriced. Overpriced properties sit empty while other properties get rented. Knowledge of rental rates is a key factor to fast rentals and quick cash flow.

- Tenant screening: A Property Management Company requires a detailed written application from each adult with photo identification. Additionally, PM’s will run criminal, social security and public notice (bankruptcy or judgments) searches to determine if the application is accurate. Property Management Company will also call past and present employers, landlords and other references. Property Management Company have set requirements and standards for accepting or declining an applicant and thereby ensuring you comply with fair housing rules and other local and state regulations.

- Marketing expertise: Property Management Company has many years of experience in how to best market properties so they are rented in the quickest time possible. Property Management Company use both offline and online marketing to maximise property exposure and find qualified tenants quicker. Property Management Companies utilises different techniques to rent a property quickly, which reduces the carrying cost of a vacant property.

- Property law and regulations: Property Management Company has extensive and up-to-date knowledge of property laws and regulations and will assist in making sure compliance with the local, state and federal rules and regulations. These rules and regulations include complying with rent control where applicable, environmental management related laws, financial regulations, etcetera. Avoiding one law suit will more than pay for any Property Management Company fees many times over.

- Tested and reliable professionals: Property management company’s will already have vetted numerous vendors, suppliers and contractors to make sure they provided good quality work at reasonable prices. Failure to properly vet these professionals can be a costly mistake. Many property owners overlook this function because they do not know how to do it or because it is a time consuming and laborious process.

- Inspection reports: Property Management Company performs property inspections before, during and after a tenancy. Additionally, most PM’s will perform routine property inspections at least every 180 days. Property Management Company usually prepares frequent written inspection reports for every property in the company’s portfolio. Faults in property that are found quickly can be resolved before they become expensive items of disrepair.

- Financial records and security deposit escrows: Property Management Company will provide detailed income and expenses reports as well as cash statements every month saving you the bookkeeping headache. Additionally, Property Management Company will also manage security deposit escrow funds and make ensure compliance with local and state regulations. Property Management Company will provide end-of-year tax reports for the property owner’s accountant or financial advisor.

- Emergency calls and shield from tenants: A property management company will shield property owners from emergency maintenance calls and tenant headaches.